SMRST v2 - radio meteor observations

In June 2009, the first radio station for monitoring meteors using the forward-scatter method ( forward scattering ) was launched at the Vsetín Observatory. The station was named SMRST ( Small Meteor Radio ScaTter ) and, with the help of a handheld receiver, it monitored meteor shower activity using reflections of signals from distant analogue TV stations off ionised trails left by passing meteors. With the gradual transition to digital television broadcasting, functional analogue TV transmitters that could be used for observations disappeared in Europe. In 2017, the last transmitters in Ukraine (Lviv) were switched off and the station ceased operations. In November 2025, a new radio station named SMRST v2 was launched at the Valašské Meziříčí Observatory. It uses the French GRAVES radar ( Grand Réseau Adapté à la VEille Spatiale ) near Dijon for meteor observations. This system is intended for tracking objects (e.g. satellites) in low Earth orbit (LEO) to build an object catalogue for military intelligence.

Introduction

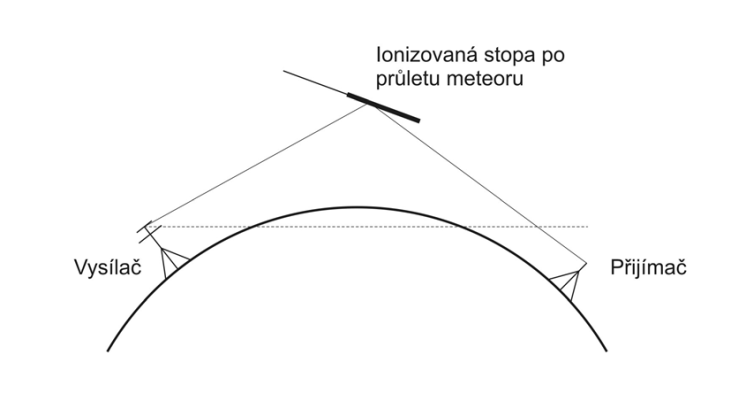

Radio detection of meteors relies on the fact that when a meteoroid passes through the atmosphere, it creates an ionised trail that for a short time effectively scatters electromagnetic waves in the VHF (very high frequency) and HF (high frequency) bands. While classic meteor radars operate in monostatic or bistatic configurations with their own transmitter ( back scatter ), the forward scattering method ( FS ) uses a geometry in which the transmitter and receiver are typically hundreds to thousands of kilometres apart and the meteor trail lies near the common tangent/mirror scattering volume (Fig. 1). In this configuration, direct line of sight between transmitter and receiver is blocked by the Earth's curvature under normal conditions, and the detected signal appears only when the meteor trail creates a suitable scattering geometry. This makes FS a relatively simple and inexpensive way to continuously monitor meteor activity, including weak shower and sporadic meteors, without the need for a high-power transmitter. Theoretical descriptions and practical implications of FS geometry (e.g. radiant selectivity and scattering height, underdense / overdense regimes, links to trail electron density) have been discussed in many studies since the second half of the 20th century and the method continues to evolve.

Method principles and measurable quantities

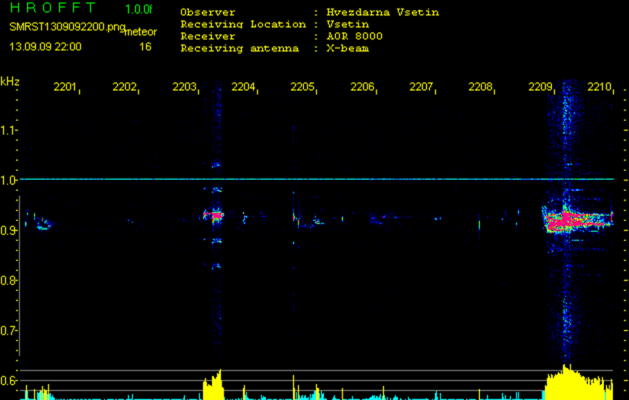

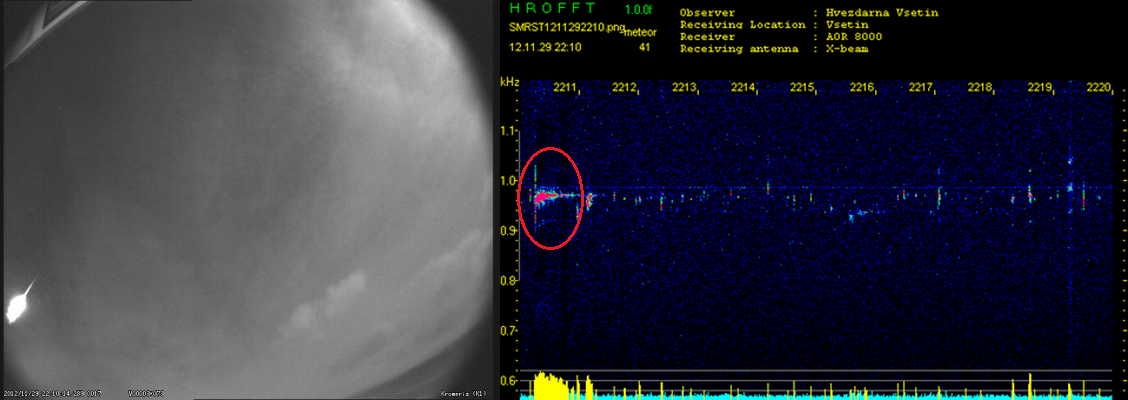

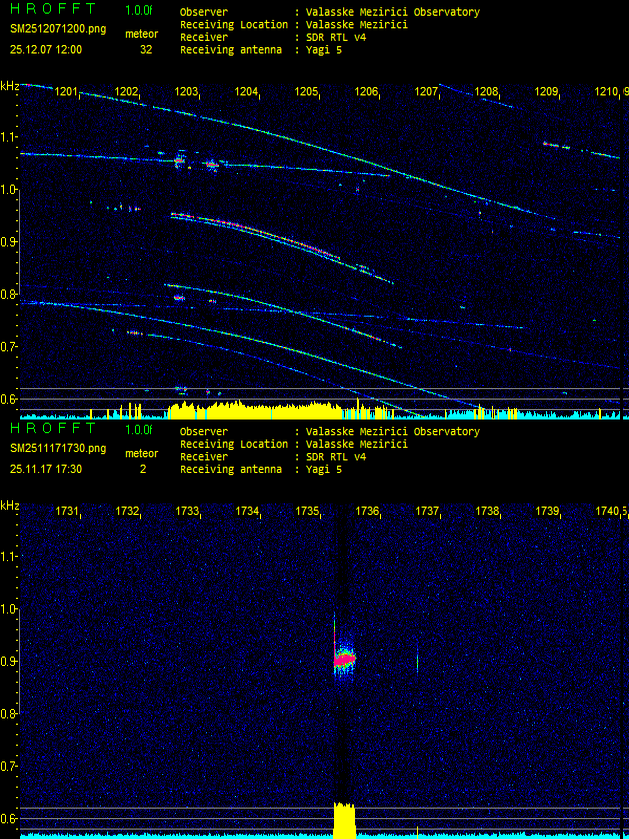

In the forward scatter configuration, short "pings" ( underdense ) and longer, fading echoes ( overdense ) are detected depending on electron density and diffusion processes in the trail (Fig. 2). From the time evolution and spectral structure, activity statistics can be derived (echo counts, durations, amplitude distributions), and in some configurations Doppler information and (under certain assumptions) height or directional parameters. A specific current research line uses continuous-wave CW forward-scatter observations to reconstruct meteoroid trajectories and velocities from signal evolution and Doppler characteristics in a receiver network. Forward scatter has the advantage over optical observations of all-day operation independent of clouds and daylight, but it also brings strong geometric selectivity (sensitivity depends on the radiant position relative to the FS volume) and dependence on transmitter and receiver parameters, which must be considered when interpreting activity and when comparing stations.

Currently usable transmitters for FS observations and the role of the GRAVES radar

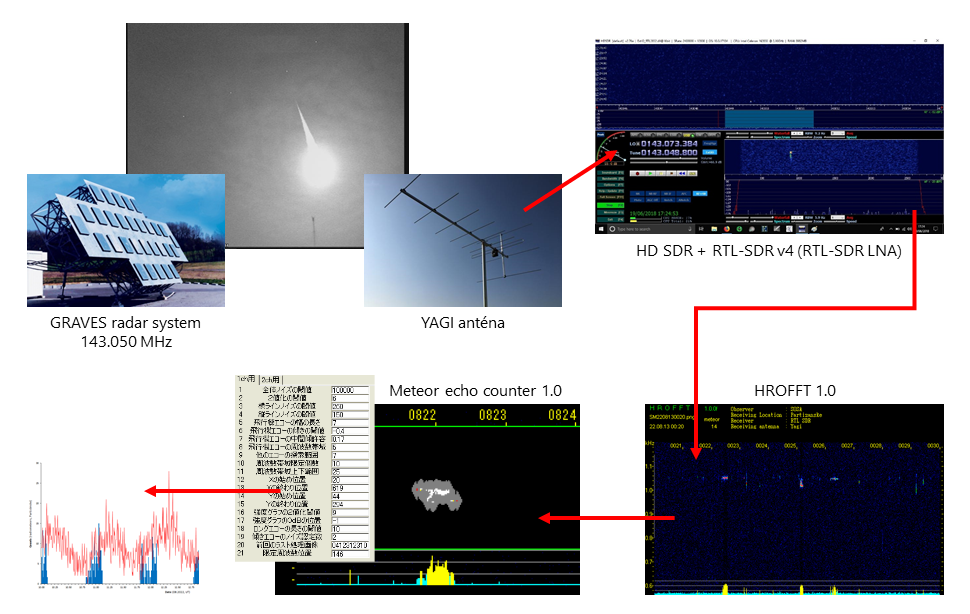

Historically, commercial VHF transmitters (TV or FM) or dedicated transmitters were often used for radiometeor observations (including the forward scatter method), but the long-term stability of these sources can change with broadcast restructuring. In Europe, the French GRAVES radar (Fig. 3) has therefore become an exceptionally practical signal source, providing a strong VHF signal (commonly listed as 143.050 MHz) and widely used by the radio amateur and scientific communities as a beacon for radiometeor observations and continuous monitoring of meteor activity. The GRAVES radar signal is also used within scientifically oriented projects that combine radio and optical data; an example is the FRIPON ( Fireball Recovery and InterPlanetary Observation Network ) infrastructure, which explicitly mentions its use for detecting and studying meteors and meteoroids. For practical FS station implementation, antenna pointing and polarisation (link to scattering geometry), receiver selectivity, and a stable time reference for long-term statistics are key. In both literature and community practice, directional Yagi antennas or multi-band configurations are commonly used with GRAVES depending on the observation goal (detection vs spectral analysis).

Uses of FS observations

Meteor shower observations and long-term activity statistics (FS systems). Forward scatter has been repeatedly used to monitor showers and estimate their activity over time, including distinguishing underdense or overdense regimes and interpreting differences in echo duration as manifestations of different meteoroid masses and structures. Frequently cited works include studies focused on FS shower observations and their physical interpretation. For specific shower campaigns, multi-year data series obtained with the FS method exist, for example analyses of Geminid activity from a forward scatter system operated for several seasons.

Deriving heights and geometric characteristics from FS data. Beyond purely detection applications, studies have been published showing that under suitable assumptions information about scattering heights and other geometric parameters can be derived from FS measurements. An example is work devoted to estimating meteor heights from forward scatter observations, which systematically addresses the relationship between FS geometry, signal time evolution, and scattering point height.

Trajectory and velocity reconstruction - modern CW forward scatter. In recent years, methods have emerged that reconstruct at least some kinematic parameters of meteoroids (trajectory and speed) from the CW signal in forward scatter geometry and discuss the usability of networked receiver configurations.

Orbit radars - related systems (CMOR, AMOR). Radiometeor research also includes robust pulsed or multi-frequency systems that detect mainly signals reflected from the ionised shock wave in front of the body itself and allow determination of velocities, directions, and in some configurations meteor orbits. A typical example is CMOR ( Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar ), which has long been used for large statistical surveys of meteor showers and the sporadic background. This broader category of multi-station radars also includes systems such as AMOR ( Advanced Meteor Orbit Radar ) and others used for detailed mapping of meteoroid flux (including weak meteoroids) and for deriving physical and dynamical properties of individual meteor populations.

SMRST v1

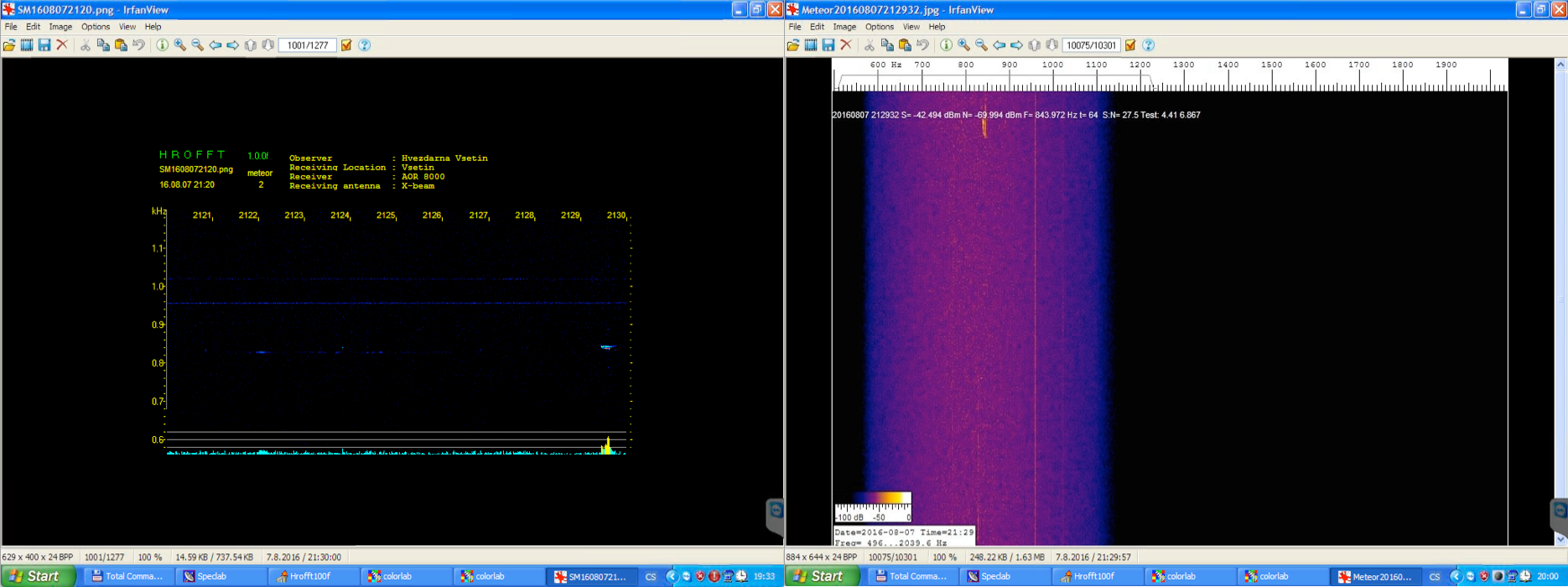

Radio meteor observations at the Vsetín Observatory were carried out using the SMRST ( Small Meteor Radio ScaTter ) system, whose first configuration (v1) was commissioned on 9 June 2009. The SMRST setup was a comprehensive passive receiving system for meteor observations using the forward scattering method, employing external TV transmitters as signal sources. The receive section was built around an omnidirectional X-beam antenna that provided stable reception over a wide angular range. The antenna was connected to a handheld wideband AOR AR8000 receiver with an operating range of 500 kHz to 1900 MHz, allowing flexible tuning to various analogue TV transmitters suitable for forward scatter observations. An A/D converter for the SpectrumLab program was used for digital signal processing; when using the alternative recording program HROFFT the converter was not required and the signal was fed directly into the computer's sound card.

To suppress interference from nearby sources, a triple LC band-pass filter tuned to TV channels I and II was included, effectively reducing the impact of strong local TV and FM transmitters. Data recording and processing were done on a desktop computer, with ColorgrammeLab or SpectrumLab used for visualisation, archiving, and online distribution (Fig. 5). The installation also included standard installation materials, especially coaxial cabling and connecting cables between the filter, converter, and the computer.

When the system was commissioned, it was initially tuned to the analogue TV transmitter Yerevan (Armenia). This configuration proved unsuitable in practice, mainly due to frequent interference that negatively affected the quality and continuity of recordings. For this reason, the system was retuned in November 2009 to the Val Venosta transmitter in Italy, which significantly improved the signal-to-noise ratio and practically eliminated interference from the analogue TV transmitter Ostrava. Further optimisation occurred in October 2012, when the system was retuned to the Lviv (Ukraine) analogue TV transmitter. This change increased the number of recorded meteors compared to the previous configuration. Except for occasional short outages, typically around local midnight, the system in this configuration operated mostly smoothly and stably.

The SMRST system in this configuration remained fully functional until 2017, when the Lviv analogue TV transmitter was permanently switched off as part of the shutdown of analogue television broadcasting. This ended SMRST operations in this form.

SMRST v2

The SMRST v2 radio meteor observation station was launched in test operation at the Valašské Meziříčí Observatory on 8 Nov 2025. After minor adjustments to cable routes, it entered full operation on 16 Nov 2025, the day before the expected maximum of the Leonid meteor shower. Signal reception is provided by a five-element directional Yagi antenna Diamond A144S5R2 (Fig. 7), with signal distribution from the antenna via a 50 Ω coaxial cable. Signal digitisation is handled by an RTL-SDR V4 USB wideband receiver with an RTL2832U ADC chip, preceded by a wideband RTL-SDR LNA signal amplifier (Fig. 6).

The HD SDR program is used to set the receiving frequency of the GRAVES radar signal and to adjust digitised input parameters (signal-to-noise ratio, software or hardware gain, etc.). From there, the signal is routed via a virtual audio input into HROFFT , which performs continuous recordings of radar activity in 10-minute intervals in *.png format.

The received signal is subject to interference (Fig. 8) from internal sources within the building (motors, fluorescent lamp starters) and external sources (transmitters, aircraft reflections). Internal interference is filtered by a socket with EMI (electromagnetic interference) and RFI (radio frequency interference) protection, while interference from external sources (especially FM transmitters) will be reduced using a DD Amtek band-pass filter (137-174 MHz). By processing outputs from HROFFT with MEC ( Meteor Echo Counter ), most of the interference that occurs when receiving the GRAVES radar signal can be eliminated.

Data processing and evaluation

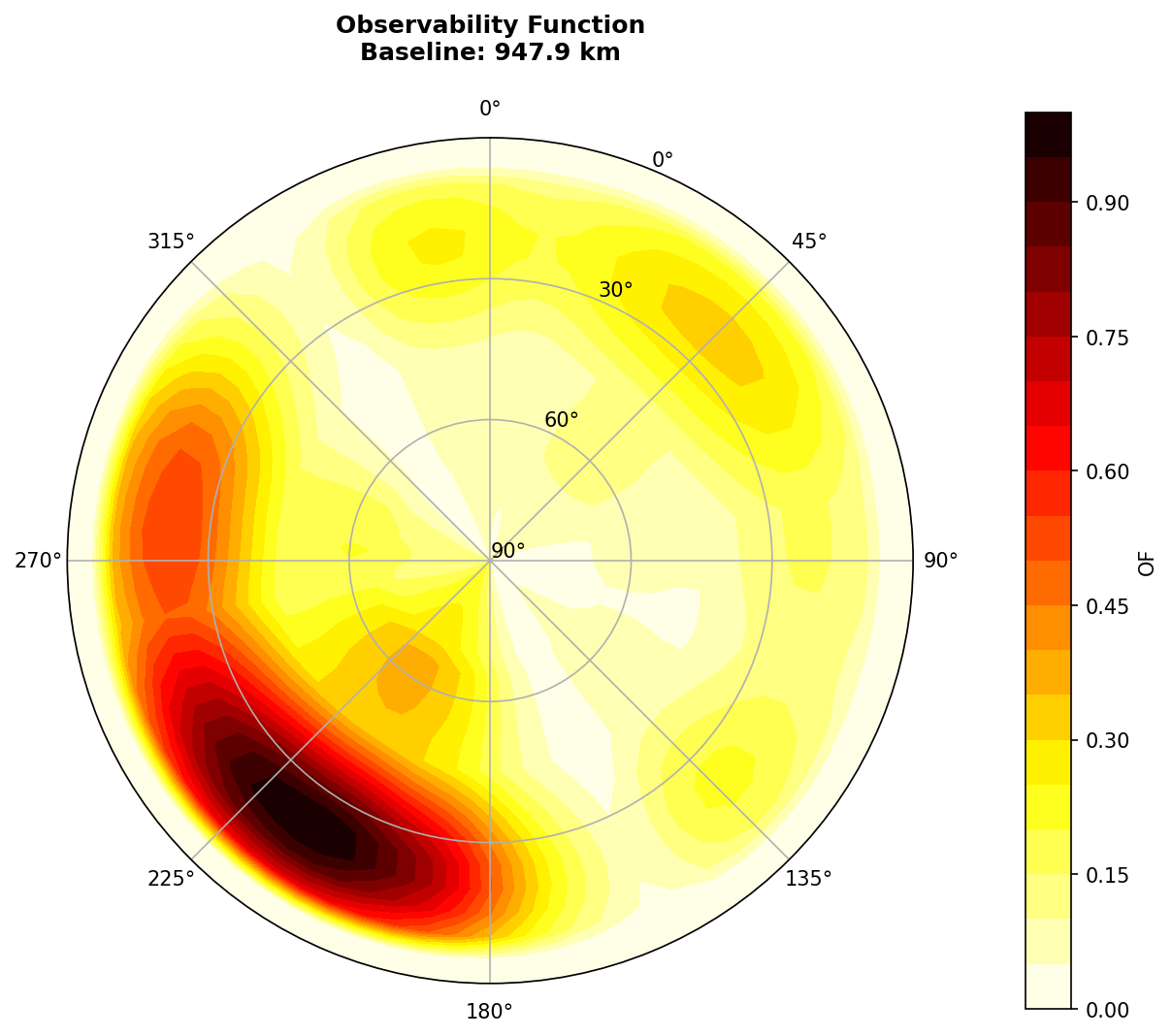

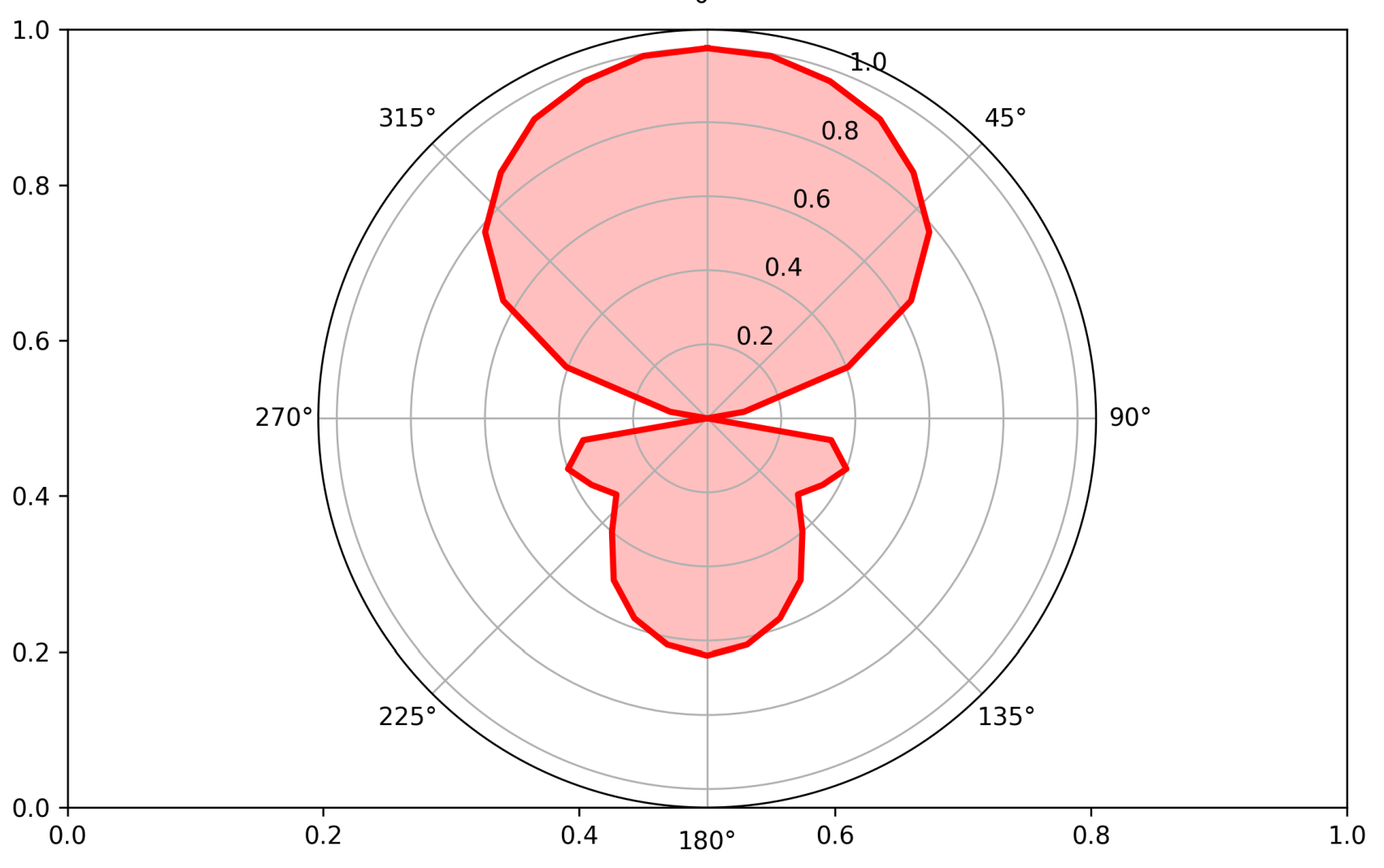

With the directional Yagi antenna used, it is necessary to consider that sensitivity (ability to detect meteor echoes) is not evenly distributed across the sky (Fig. 10). The geometric configuration of the transmitter-receiver line and antenna directivity create a detection sensitivity function dependent on position that must be quantified. The observability function ( OF ) characterises this sensitivity variation and enables calibrated calculations of the corrected hourly zenith meteor rate ( ZHR ) from echo counts after evaluation by the MEC program. The transmitter ( GRAVES ) - receiver (Valašské Meziříčí Observatory) line has a length of 948 km at azimuth 260.4 degrees from the receiver. The antenna is oriented at azimuth 240 degrees with elevation 12 degrees, causing a 0.8 dB attenuation of the transmitter signal. The OF function therefore reaches its highest values at azimuth 215 degrees and elevation 20 degrees (Fig. 9). Another applied correction is the sin(h) function, i.e. the instantaneous radiant height above the horizon.

A very important correction in analysing meteor shower activity is subtraction of the sporadic background from the total observed rates. Reduction by the sporadic background is performed before correcting the observed counts by the OF function and the radiant height above the horizon sin(h) . The ideal period for fitting the sporadic background based on observed data is a period of low shower activity, and data from the Juliusruh radar in Germany from 1990 to 2003 were used as a basis, characterising both daily and annual variations of sporadic meteors (Fig. 11).

Results - Geminids 2025

The Geminids are one of the most active and reliable meteor showers of the year. In 2025, their maximum occurred on the night of 13/14 December 2025. The parent body of the shower is asteroid (3200) Phaethon. Geminid meteors are of medium speed and under ideal conditions up to 150 meteors per hour can be seen.

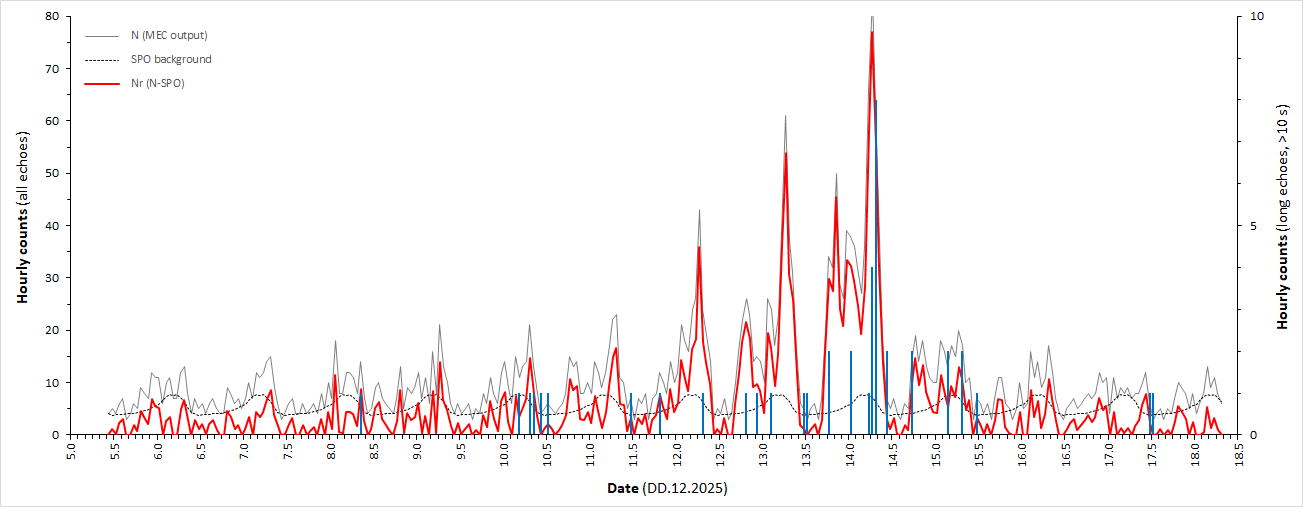

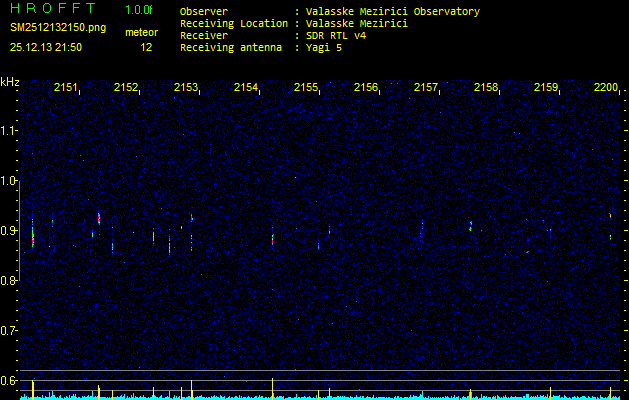

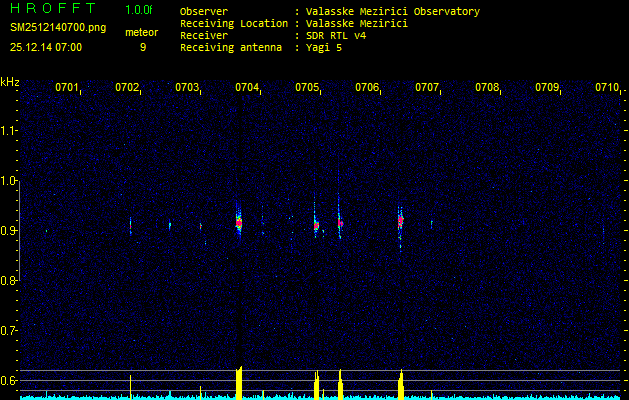

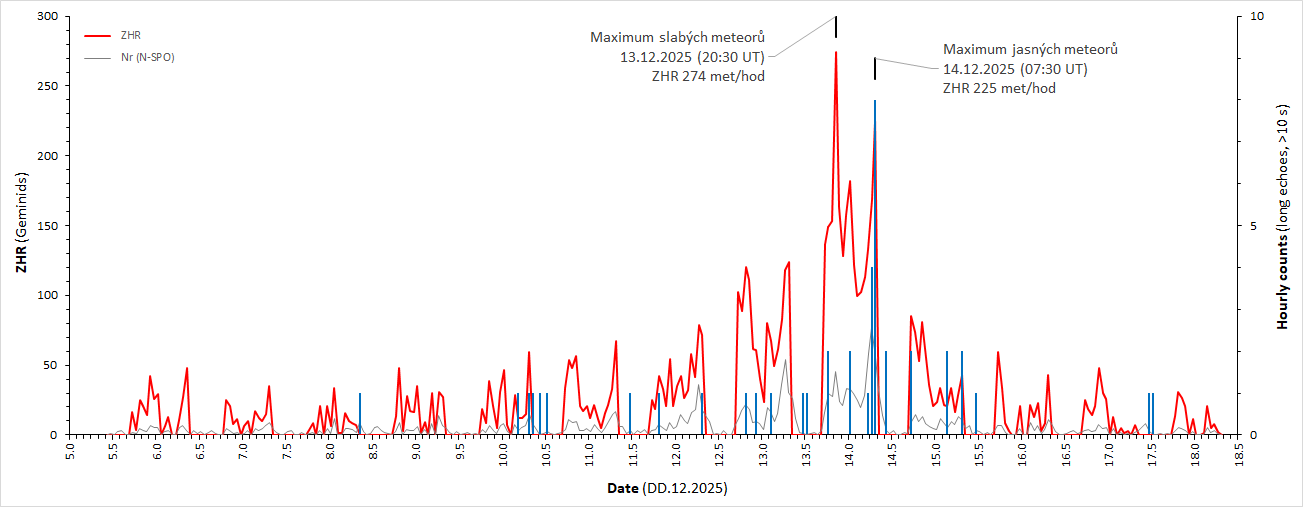

Observations of the Geminid maximum with the passive radar SMRST v2 show a sharply defined maximum night (13/14 Dec 2025). The ZHR (corrected hourly zenith rate) on the night before the maximum reached only 45% of the ZHR on the maximum night. A clear 11-hour delay is seen between the maximum of bright (visual) meteors and faint (radio) meteors, which is common for strong showers. Bright meteors are defined by echoes longer than 10 s, often overdense echoes (Fig. 13). Faint meteors ( underdense , Fig. 12) are defined as short echoes. In 2025, the maximum ZHR of radio meteors was 274, representing the maximum of faint meteors on 13 Dec 2025 at 20:30 UT. The maximum of bright meteors was lower, with ZHR reaching 225 meteors, occurring on 14 Dec 2025 at 07:30 UT (Fig. 14). This result is consistent with visual observations of the main shower maximum, which according to the IMO ( International Meteor Organization ) occurred on 14 Dec 2025 at 06:10 UT ( ZHR 148 meteors). A secondary maximum corresponding to the radio maximum of faint meteors was observed on 13 Dec 2025 at 20:10 UT ( ZHR 109 meteors). In the Czech Republic, the weather on the maximum night was very unfavourable, which prevented both visual and camera observations of the Geminid maximum.

author: Jakub Koukal